Blog Archives

Using Minor Pentatonic Over Non-relative Major Chord Progression

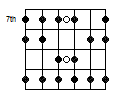

Recently, I was messing around with different riffs while playing against some new backing tracks I found. I was playing around in the key of A major and the F# minor pentatonic just wasn’t sounding right to me. It was missing something. Oddly, at the moment, I had a melody pop in my head that sounded good with the backing track. As I started hammering it out on the guitar, I realized I was playing the A minor pentatonic over the A major chord progression and it sounded perfect!

As I played on, I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. This totally blew all the rules of music theory out the window as I should have been playing F#m over A or Am over C. I dug into it a little further and found something very interesting. A major and C major have all the same notes except three in common; F#, C#, and G#. Because of the rest of the notes being common, my ear couldn’t tell the difference. The three that were not in common added just enough tension that my ear wanted to hear so it sounded better with that tension than without.

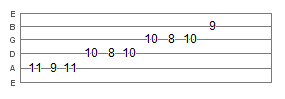

Below is the riff I came up with. It’s a six bar version of the 12 bar blues progression. I recorded several different strummings with the same chords and played the riff against them all. None of them sounded like they didn’t belong together.

Give the riff a try. If you can, record the chord progression as I have labeled and play the riff against it. Or, try your own combinations. See if a C# minor pentatonic scale sounds good over a C# major chord progression. You may find, as I did, the possibilities are endless and it will give you a new sound.

Tuesday Night at the Improv

Recently, I was thinking of ways to teach my students better improvisation skills. Some were catching on to what I was teaching, but others seemed to not have a creative bone in their body. After a bit of brainstorming, I realized it was something they missed when I was teaching scales.

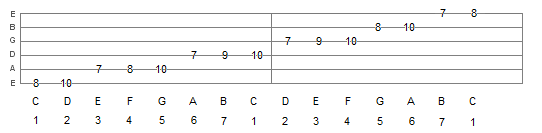

Take the C major scale below. You can play every note, you can play the pentatonic, or you can play random melodies. There is so much you can do, you just have to experiment. I told my students “Keep it simple. Most solos sound complex because the guitarist took something simple, built upon it, practiced it until they could build up the speed that it’s being played at, and what you hear sounds someone who is totally shredding the guitar when they are hardly putting in any effort into playing the solo.”

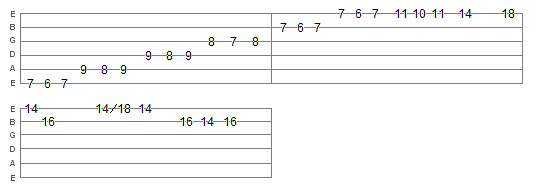

My challenge was to come up with something “from string to string”, not “back and forth between the strings”. One student saw what I was looking for. He took the scale, then selected the notes shown in red below:

My challenge was to come up with something “from string to string”, not “back and forth between the strings”. One student saw what I was looking for. He took the scale, then selected the notes shown in red below:

Now that he had the notes he was going to use, how would he play these from string to string; meaning playing from A to D to G to B instead of going back and forth between the strings? Below is the lick he came up with:

Now that he had the notes he was going to use, how would he play these from string to string; meaning playing from A to D to G to B instead of going back and forth between the strings? Below is the lick he came up with:

For those of you Foreigner fans, this is similar to the solo for Cold As Ice:

Both solos, although similar, are also simple. There are no shifts back and forth from strings on the run up, there are no bends or unison bends, and there are no chord shapes. If my student would have kept the same pattern going, he could have created something that sounds very similar to Cold as Ice, but with a different spin. This is how solos are created. You take patterns, whether someone has already done it, or if you find it’s something new, and expand upon it. Eventually, you have something unique to you that you can play in any key.

Once my students realized that they were missing patterns within the scales they had been practicing, and that they can take those patterns, develop a lick, or a series of licks, they can then put them together to form a solo. This is truly what improvising is all about. When playing against backing tracks, these students became more confident in their solos.

What is behind the 1-4-5 rule?

I’ve had several students ask me “What is behind the 1-4-5 rule?” For this, you have to understand how basic music theory works. “Ugh…what is with everyone trying to ram music theory down my throat? Just teach me how to play guitar!” Well, in this lesson, if you can’t listen to a song on the radio, pick up your guitar, and start playing along, maybe guitar isn’t for you.

Everyone thinks learning to play guitar means to learn how to play chords first. While that’s a good approach, how do you know where and when to use them? I teach scales first…especially the C scale seeing as it has no sharp or flats.

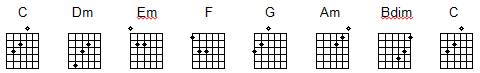

In the C scale, you have 7 notes: C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. If you consider these numbers from 1 – 7, C would be 1, D would be 2, and so on. Knowing the names of the notes in the scale, we can now develop chords by using the 1-3-5 method. To make a C major chord, you take C, E, and G (1-3-5 notes of the scale). If you take the 2-4-6 notes of the scale (D-F-A), you would get the D minor. Again, if you take the 3-5-7 notes (E-G-B), you would get the E minor chord. Continuing on, you would eventually end up with what is called the “C major chord progression”, as shown below.

How does this help with the 1-4-5 rule? Well, now that we have chords to play, we can actually play a song. How many songs do you know of that are purely solos or melodies? Not many, I’m sure. The 1-4-5 rule allows you to take the first, fourth, and fifth chord from a chord progression and make a song out of it. Don’t believe me? Play the C chord, followed by the F chord, then the G chord. Almost sounds like Twist and Shout, or Labamba. Or, try playing G-F-C-G.

While no songwriter really sits down and says “Okay…I need to use the 1-4-5 rule to write all my songs, and I’m in the key of C, so I need to use C, F, and G,” it does form the basic building blocks of many songs you hear.

What about minor progressions? It’s the same thing. If you know the relative minor of C is A minor, you can figure out almost any song in the key of A minor by looking at the following progression:

Now, your 1-4-5 would be A minor, D minor, and E minor. All the same chords as in the key of C. No, you do not need to stick with 1-4-5, but it will help you learn to play almost any song you can think of, or create your own.

I hope this helps. And remember: a little music theory goes a long way.

Guitar a la Modes

Most music is created off the top of the artist’s head, the rest is a collective brainstorm to produce a song that’s current with the times. Either way, many musicians don’t sit down and draw a song out like an outline for a business plan or a blueprint for a building, it just comes naturally. However, there is some planning and musical theory that goes into a song and part of it has to do with modes.

Modes are scales and chord progressions that are produced by moving the starting point of a scale or chord progression without changing its formula. Take, for instance, the C major scale (C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C). This orientation of the scale would be considered the Ionian mode, or major mode. This mode can be used in many forms of music. The chord progression for this mode would be C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, Bdim, C.

If we move up one position in the scale, we get what’s called the Dorian mode. This is most commonly heard in jazz and jazz/rock where it’s used in soloing over minor seventh chords and sounds like the natural minor with a raised sixth. Nate Richards from Richards Guitar Studio has a video that discusses the Dorian mode more in detail and explains how it’s used in modern music. You can read more about it at Modes for Guitar – Example in Dorian. Notice nothing changes except the starting position. The scale is D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D and the chord progression is Dm, Em, F, G, Am, Bdim, C, Dm.

The third position will give us the Phrygian mode. You would typically hear this in flamenco music, which sounds like a natural minor with a flatted second. Again, nothing about the C major scale changed except the starting point, so the scale would be E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E and the chord progression would be Em, F, G, Am, Bdim, C, Dm, Em.

Building off of this theory, the rest of the modes can be briefly explained. The fourth position gives us the Lydian mode, which sounds like the major scale with the exception of the sharped fourth. This mode is used in jazz to solo over major seventh chords.

The fifth position gives us the Mixolydian mode, which also sounds like a major scale except for the flatted seventh. This is heard in a lot of folk music and modern rock music.

The sixth position is the Aeolian mode. Note that this is also the relative minor of the scale or chord progression. In this case, it would be the Am chord for the C progression.

The seventh position is theLocrian mode. It was avoided for many centuries because of it’s diminished chord preventing melodies to never truly come to rest. This is mostly heard in jazz soloing over minor seventh flat five chords.

Test these modes out next time you practice. Try an F Phrygian by starting on the third position of the D flat scale (Fm, Gb, Ab, Bbm, Cdim, Db, Ebm, Fm) or an D Mixolydian by starting on the fifth position of the G major scale (D, Em, F#dim, G, Am, Bm, C, D). The possibilities are nearly endless.